After my first year of college, I decided not to go back but had full intentions of returning at a later date, when I was ready. At that point in my life, I wasn’t. I was uninspired, unmotivated, indecisive and without focus. I changed my major so many many times during that year that my Dad began to refer to it as my “major of the month.” The only decision that seemed right to me was my decision to not return.

My parents were on board, especially my dad, which surprised me, as he was a high school guidance counselor and part time community college counselor who promoted higher education, yet at the same time was able to recognize when a student was struggling. If I wasn’t going to return to college, my parents said I needed to have a plan. I wasn’t good with plans. I wanted to see what would come my way without having to put a lot of effort or decision making into it. The wait and see attitude was realigned when my landlord parents started pushing me to find find a job with a little more permanence than what I had shown them thus far. I had landed a temporary job as a nanny in Chappaqua, NY for the summer, but once back home, was in need of something more permanent so answered an ad in the local newspaper for a position as a receptionist at a nearby regional airport/flight school. It wasn’t at all what I had in mind, but my landlord parents were happy so I said yes and started working at KC Piper. I didn’t care for the job – answering the phone, booking flight lessons and taking money from pilots who bought fuel, but I told myself that I’d make it work until I could find something more suitable. I felt disconnected and out of place in the place where I spent most of my day until one of the flight instructors asked me if I had ever been up in a small plane and if I hadn’t, I should definitely take advantage of the $5 introductory ride. He, and his staggering good looks, were my point of interest, not the 15 minutes of being airborne, and so I agreed. It didn’t take long once in the air to realize that I was far more captivated by the act of flying than I was with the handsome pilot and before we even began to taxi back, I decided that although it was far beyond my reach financially, and I had no idea how I was going to make it work, I was going to learn how to fly, and the cute instructor that sat to my right was going to be the one to teach me. And so that’s how it started. For the next several months, I begged, borrowed and stole every left seat hour I could muster, while saving every single penny of my hard-earned low wages. I had a plan. It wasn’t exactly what my parents had in mind, but it was a plan.

I was young, barely 20, and idealistic. My dreams were as big as my check book was small but somehow I knew I could make it work. Unquestioning optimism at its finest. I was at the right place, at the right time and in that short 15 minutes of flight time, there was never a question as to what I wanted to do. I wanted to become a pilot.

It was hard. It was exhilarating. It was inspiring and I loved every minute of it. I was a good student who became a good pilot and was often complimented on how strong my “seat of the pants” abilities were, which I would later learn had nothing to do with how my seat looked in pants but rather, was a measure of natural judgement and instinct without the use of instruments. Did I mention that I was barely 20 years old and terribly naive? I didn’t even know to be embarrassed by the many faux pas I would stumble over as I truly didn’t know what I didn’t know. Case in point, my first experience of night flying. As I was taxiing in after landing, my instructor asked me why I was hugging the far edge of the taxiway and not in the center of it where I should be. Was I having a hard time seeing it?

“Oh not at all! I was trying to avoid the light bulbs as I didn’t want to break them.”

The lights I was referring to were the ones that were embedded into the surface of the taxiway, but honestly, from where I sat they seemed to protrude from the surface, which was why I was trying hard to avoid them. I’m guessing he hadn’t encountered this situation before or he would had advised me ahead that I could taxi right over the lights and they wouldn’t break. A few days later, and with the same instructor, I couldn’t help but notice that he was fixated on something outside of the airplane. After being in the air for only a few minutes, he turned to me and with a very puzzled look on his face asked me if I had untied the tie down ropes on the plane and if so, how did I do it? Planes are tied down to the ground with heavy ropes to keep them steady during storms and winds and when untying a plane during the flight pre-check, the ropes are untied from the wings. Given that it was my first time pre-flighting the plane alone, I did what I thought was the right thing and I untied the ropes from the heavy ground anchors, which left the tie down ropes flapping from the wings of the plane as we flew rather than remaining on the ground where they belonged.

I answered by telling him that yes I untied the plane and boy were those ropes ever hard to get undone! He chuckled, kindly, so as not to make me feel embarrassed but no doubt the story had worked its way around the break room by the end of the day. Obviously, I hadn’t been paying attention when that section of the pre-flight operation was being explained. Evidence that sometimes I learn things the hardest way possible. Again, I didn’t know what I didn’t know and honestly think that bit of naivety is what kept me in the game. My parents worried about the large financial investment I was making, especially if I didn’t follow through to actually obtaining a license. They had every right to think that as quitting before finishing was an established pattern for me. But this felt different. There was just something about flying that touched my soul of souls and awakened a part of myself that I had never felt before.

After what seemed like a very short 6 weeks, my flight instructor told me it was time to take to the skies alone – time for my first solo flight. Student pilots aren’t told this ahead of time simply because of anxiety issues but I knew it was coming. There were a lot of emotions that day, but I have to say, fear wasn’t one of them. I was ready. Although this is a very big deal for student pilots as there is no instructor sitting right seat for security, the initial solo flight is a short one that consists of a few trips around the airport landing pattern doing touch and goes – a touch down landing then immediately taking off again and repeating the process. It was recorded in my log book as .4 of an hour – 25 minutes of just me and the airplane. 25 minutes of pure joy, and tremendous pride. 44 years later and I still smile when I think of my young, very naive self in the cockpit of a Piper Cherokee 140, tail number N5606U, chatting nervously to myself with a constantly nodding of my head up and down in a HOLY COW, YOU’RE DOING THIS!!!, manner. The tradition that follows a student pilot’s first solo flight is to cut the shirt tail off the student’s shirt, which is then labeled and displayed as a “trophy.”. This tradition originated in the days of tandem trainers when the student would sit in the front seat and the instructor behind. Because there were rarely radios in the planes, the instructor would pull on the student’s shirttail to get his (or her) attention then yell in his ear. A successful first solo flight is an indication that the student can fly without the instructor so a shirt tail would no longer be needed and so the tradition of cutting it off began. I proudly backed myself up to my scissor holding instructor, while wishing I had worn one of my own shirts and not my sisters, who by the way was more angry about her ruined shirt than she was thrilled about my new accomplishment. It was a navy and white checked, long-sleeved, broken in with love and now damaged shirt that I wish I still had, even though it was never mine, missing tail and all.

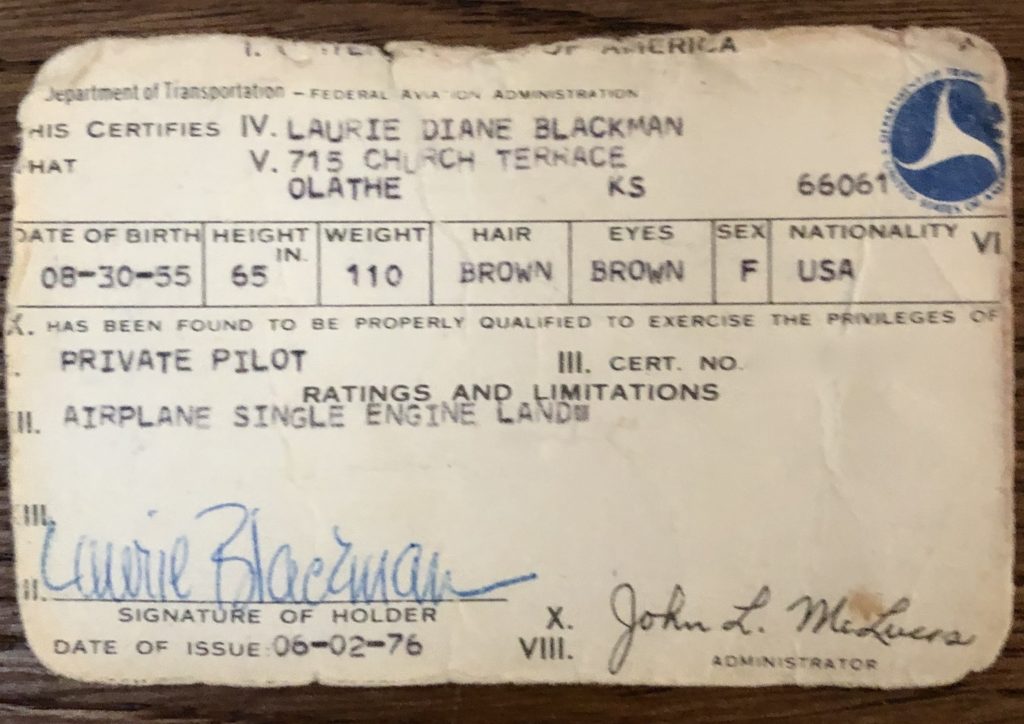

6 months after soloing and 7 months after my introductory flight and after passing a grueling written exam, a physical exam and flight exam, I got my private pilot’s license. The next day, I rented a plane and took my younger brother and sister up flying. We flew to Topeka, Kansas, a mere 57 miles away, to get a coke because that was the kind of stuff you could do when you were a pilot. My little brother got sick, but fortunately for me, my sister was wearing a bandana and as the pilot in command, I instructed her to take it off immediately so her brother could throw up in it. I was learning that passengers bring on a whole other set of responsibilities and worries when you’re the pilot in command, and that bandanas or maybe air sick bags would be a good thing to have on board. The following day I flew my parents to Emporia, Kansas, farther than Topeka by 30 miles. This journey was my debut – to show off my skills, but even more importantly, to show off my completion of something I had started on a whim and a hope. A start to finish completion. Finally.

Two years later that license that I earned was far more relevant than the college degree I hadn’t earned and I landed a job as a regional sales manager in the avionics industry. Instead of a company car, I flew the company airplane to various airports to demonstrate, sell and basically show off the King Radio avionics systems that I had in my airplane. The most challenging part of the job wasn’t the flying, but rather, was earning respect from the dealers who questioned who was making the sales calls every other week. I was too young (24) and the wrong sex. More than once I was told by a shop manager that he was just going to wait until the following week when my partner, a man, would be visiting. There wasn’t much I could do in response but leave politely and make the note in my follow up report that I tried. I knew I was adept at selling the product and offering any customer support that was needed, but getting in the door was often my toughest challenge. It felt like I was working twice as hard as my male counterparts before my job even began.

Management decided that I needed to adhere to a dress code as all the other sales managers did when out in the field, which I totally expected, but what I didn’t expect was that my dress code was a dress or skirt and not the more appropriate slacks, which was what I had hoped for. This made for awkward situations when I’d enter or exit the plane while trying to maintain a modicum of modesty. I never knew how I’d be accepted or regarded when calling on the avionics shops at airports for the first time, but the one thing I could always count on was the handful of men staring with curiosity as I carefully stepped out of the short narrow doorway, onto the wing then onto the tarmac in a dress and I’m guessing, as I can’t recall, most likely in inappropriate shoes because I was 24 and that’s what 24 year-olds did. I was the first female regional sales manager at King Radio and the management wasn’t exactly sure what to do with me as I didn’t fit the mold they were used to – i.e. men in suits, hence the dress requirement. I didn’t have the confidence to question why I had to wear dresses when my counterpart were wearing slacks, but I was one person, and a girl no less, going up against a company of men and I knew I’d lose so dresses it was and comfortable when entering and exiting a plane, it was not.

My daughter asked me recently if I had bigger plans when I set out to get my pilot’s license… you know, to become an airline pilot some day perhaps? I’ve thought about that a lot even though I gave her the first answer that came to me, which was no. I did have a job in the field of aviation, just not one that held the perceived glamour of passenger carrying jet pilot. Although I did get a lot of kudos and “atta girls” during my short-lived dip into the field of aviation, there didn’t seem to be room for a female in the all male, good ole boy network that I had become a part of, leaving me feeling like I was always flying solo without a guide, a mentor or even a map most of the time. I’ve saved the articles that came out in avionics magazines and newspapers that introduced me as the “first female regional sales manager in avionics” that went on to add that there was “something prettier on the runways to look at these days.” It’s hard to believe today that those words were even written. Even though I was still very young and somewhat naive, I was learning a lot and not just about avionics. I had to wonder, if King Radio was so happy to take the credit for being the first avionics manufacturer in the country to add a female to their sales force, why weren’t they willing to stand up for that female and mentor her in these new, unchartered waters? The evening I spent in a topless mermaid bar with a group of “fellow sales managers” somewhere in the southeast, because I was told that was what sales managers do, with nary a warning or an apology to me, was the beginning of my end at King Radio. I realized that as much as I believed in the product and loved getting to fly in an overly-loaded top of the line airplane, I was never going to feel totally comfortable in the environment I was in, regardless of how much I tried. I lasted 2 years then left King Radio for new horizons, packing up my ’74 VW for a move to Phoenix, where my sister with the ruined shirt lived. After a year, I left Arizona for a job in Alaska after realizing that I really did hate hot weather, but that’s another story.

Before I worked at King Radio, flying was a time of dreaming and complete freedom for me and I cherished the moments during a flight when it was clear skies ahead when nothing needed attention except the unfettered beauty that would surround me at 3,000 to 6,000 feet above the ground. Those were the moments – almost as if time had stopped for me simply to take it all in. And I would. My imagination would soar like a Piper Cherokee with a tailwind as I scanned what felt like the entire world through the windshield of the small plane.

It was also the time when I met Leigh, my kindred flying spirit. She was taking lessons at the same time I was and we immediately bonded over our passion for the new hobby we had both immersed ourselves in. We’d go to the airport at night, park as close as we could to the runway and with Judy Collins wafting from the radio, would watch the bellies of planes as they descended onto the runway while laying on the hood of the car. It was our entertainment, our inspiration and a connection that remains today. Neither of us talked about aviation as a career but instead simply embraced it with our eyes to the skies and our souls in the clouds. We could recite every line of John Gillespie Magee’s “High Flight” poem that began, “Oh I have slipped the surly bonds of earth, and danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings,” the line that always gave us pause. Leigh was in the very small group of people who understood what I was doing and that we didn’t have to have a reason why or an end goal, because flying was enough. We carried our pilot’s licenses in front of our driver’s licenses in our wallets because it was the piece of paper that held more pride for us than any other and spent far too much time (or not enough?) fantasizing about piloting a hot air balloon across the country in celebration for the bi-centennial that was approaching. It was the period in my life that I call my aviation experiment and although the last time I flew alone in a small plane was in 1979, I still crane my neck around to get a better look at the instruments when passing by the cockpit when I step onto a plane and am stopped in my tracks when a small plane flies overhead, simply for the pause to capture a memory.

Learning how to pilot a small airplane was less about acquiring a skill that could open doors for me and more about slipping my own surly bonds and seeing what flying on my own wings felt like, with or without an airplane. I’m often asked if I miss flying and if I’ll ever get current so I can fly again and to that I have to answer yes and I don’t know. Those wings that were discovered in the small cockpit of a Cherokee 140, are still with me, holding me aloft and giving me strength and a continually changing prospective. I not only learned how to control the parts of an aircraft to make it fly, but I also learned how to find my own wings with the confidence that my internal compass will always direct me towards clear skies and tailwinds.