One thing I’ve learned over the past seven months about grief is the effect it has on the brain. I’ve gone through periods of not being able to watch movies or read books because I couldn’t follow even the simplest of plot lines. I’ve had conversations with people I don’t remember, made appointments I didn’t remember, and forgot to show up to appointments because I forgot to look at my calendar. Things happened in the first few months after Emery died that I wouldn’t have known if someone hadn’t told me. Recently, while trying to organize my writing folders on my computer, I came across a letter I wrote to Emery on February 4th, one month after she died. I wrote it while staying in Portland at Thomas and Brooke’s house. I remember little about that trip, except for a lot of sleeping and taking a few short walks in Hoyt Arboretum with Thomas. I didn’t remember writing the letter, but I thought it would become familiar when I read it. It wasn’t. It was as if I was reading what someone else had written for the first time. It made me cry.

On the 7th month anniversary of Emery’s death, I decided to share the letter (I don’t like the word anniversary as it feels too celebratory to me, but I’m not sure what else to call the collection of dates that have marked the time). My grief edges have softened somewhat since I wrote the letter, but I still carry the same ache of sadness and grief that I did when I wrote it, one month out. My words matched my scattered emotions, and as I reread them, a clear picture of someone trying to come up for air but going deeper and deeper into the water emerged. I wanted to edit it, clean it up, choose different words, but decided to let it stand as it was — a snapshot of my heart and soul in recovery mode.

February 4, 2025

Dear Emery,

One month ago today, at 11:38 am Mountain time, you left us. It feels like forever ago and like yesterday at the same time. Time has lost its meaning, as has so much else in my life. The grief of your death is so deeply woven into who I am right now and who I am becoming. I don’t recognize myself. My heart is in pain, and my physical body is showing that pain. I’m exhausted, my body aches, and I’ve aged ten years in a month. All I want to do is sleep. I look forward to crawling under the covers, whether at night or during the day, because those are hours of escape for me. Since you died, I have woken up almost every night at 1:00 am. My sobbing wakes me, and I have a desperate need to hug you, to have you be alive, for just a few more moments. It feels like a plea to a greater power…just one more moment, one more hug, one more telling you I love you. And then I wipe the tears from my face and fall back to sleep again.

So often during the day (and night), I think of things I want to tell you; usually, random thoughts that come to mind. I still reach for my phone to text you. I should text them to myself, but I don’t because without you on the other end of the text, sending back a laughing emoji or responding with the name of the person, the restaurant, the brand of clothing, or you telling me why you disagree, there’s no reason. My random thoughts no longer get a response, so I keep them to myself. I had no idea, and why would I, the vacuum that would be left in your absence. I don’t know what to do with it or how to fill it. I know, it’s only been a month, and my job right now is to feed myself, sleep, and breathe, and that feels like enough right now. My heart broke when you died, sweetheart, and right now, sitting in bed in Thomas and Brooke’s wonderful guest suite (that I’m so sorry you never saw), I don’t feel like it will ever be OK again. Honestly, that is terrifying to me —terrifying that I may feel like this for the rest of my life. Life feels so hard.

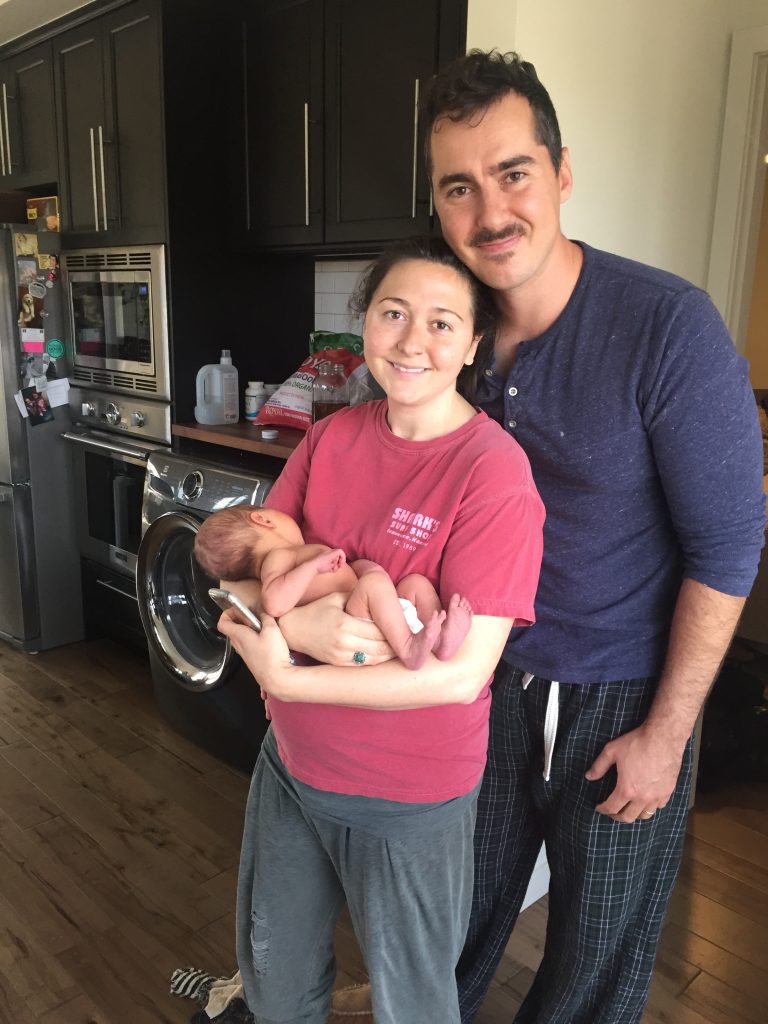

I miss you desperately… your wisdom, humor, advice, and reminders that we should all lead with kindness and love. Watching you in your role as Arlo and Muna’s Mama gave me such pride, and I saw a lot of myself in your parenting, although you did it with far more patience than I did. Muna is so much like you in both her appearance and her personality, and sometimes I feel like I’m looking at five-year-old you all over again.

I love you dearly, and I know you knew that, but still… did I say it enough? Show it enough? Yes, you’d tell me. You did, Mom, and I love you too, and it is because of that love that the grief now is almost unbearable. You’d tell me to give purpose and meaning to my grief. Give it words, you’d remind me that my words are my strength, and how I make sense of the world. You would tell me what I need to know and already know because you know my heart.

Thomas and Grant are holding me up, Emery. I lost my daughter, but I haven’t forgotten that they lost their sister. It makes me sad that I’ve been unable to help them as much as I should as their mom, as they also have broken hearts. We became a cocoon of love and support in Boulder after you died, and are still cocooning, even though we are not all in the same place. We need each other so much in your absence.

I long for one last hug. Your Dad told me when we said goodbye to you on the morning of January 4th, it didn’t feel right to leave you without hugging. He was right. We always hugged when we left each other. It’s impossible for me to think that it will never happen again. When did I last hug you? I think it had to be on Christmas, as you didn’t want me near you once you were back in Boulder. You had the flu and didn’t want me to catch it. I kept my distance. I wore a mask.

I will always be confused by your death. We all are. You were glowing and happy and full of life on Christmas, even though you couldn’t hide your sadness as I know you missed your Grandpa. Six days later, I’d watch paramedics take you out of your house on a stretcher to an ambulance that waited in your driveway.

I think of you with your beautiful eyes, ridiculously long lashes, and your smile. Oh that smile… I also think of you in the bed in the ICU at St. Joseph, hooked up to machines and intubated. I wish I didn’t. When I first started replaying those short and very long 2 1/2 days, with you hooked up to machines that were keeping you alive, I hoped with each recollection that maybe the ending would be different. Magical thinking, I suppose, but the ending never changed. As your Mom, I wanted to take your place, take the moments of fear you had as you tried to breathe, even with an oxygen mask on. I used to tell you I’d step in front of a moving train to save your life — something you didn’t understand until you had children, and when you did, we never talked about that, because why would we? I’m sure you would have said the same thing about Arlo and Muna. And yet, there you were, in a bed in a hospital in Denver, and I couldn’t do anything but softly touch the small part of your arm that was free from tubes and needles, while you lay in a bed, intubated and sedated. That train was coming down the tracks, and I couldn’t step in front of it to save you. Nor could Miles, your Dad, Thomas, or Grant, but we tried in our words to you and our words to a greater power.

I know this will not be the last letter I write to you, because you feel closer to me when I write, but not getting a response will be hard. It’s another I will have to endure.

I love you, my darling girl. So very deeply.

Mom