Frisco, Colorado August 2013

Boulder, Colorado, July 2025

I am awed by the power of a rainbow…how it stops people for a brief moment to look up to the sky in wonder as if seeing one for the first time. It’s a deep sigh, a collective awe, and for a moment, nothing else matters but the arched prism of light in the sky. I’m one of those people. It feels mandatory to me, like I will be missing something if I don’t. Because I will.

A few weeks ago, on a day that was particularly difficult for me, I was in a restaurant with Arlo, Muna, and dear friends of Emery’s, having dinner, when the rain started coming down in sheets. It ended in a matter of minutes, as it often does in Colorado, and the sun came out with a different brightness than before the rain. When the light in the restaurant shifted, Arlo and Muna abandoned their hamburgers to run outside for a look. Moments later, Arlo came running back into the restaurant and said, “Laudie, come quick! Your dream has come true!” And as quickly as he ran in, he was gone again as he didn’t want to miss one second. My grandson knows me well; he’s Emery’s son after all. I followed him to where Muna stood, dripping wet with her eyes fixed on the sky in awe of the beautiful rainbow forming above my favorite coffee shop on Pearl Street. I held back tears as I looked back and forth to Emery’s two children and the rainbow that had stopped them in their tracks. I was looking at more than a rainbow. Because of its perfection in timing, and being with the right people when it appeared, it will be a rainbow in a long line-up of rainbows that I will remember.

My history with rainbows began in Colorado. Maybe I saw them before, when I was living in northern Missouri as a young child, or in Olathe, Kansas, but they weren’t memorable, and I was too young to remember rainbows when I lived in Evergreen, Colorado. Or maybe I didn’t care about rainbows then like I do now. Rainbows for me have always meant Colorado to me.

Several years ago, before I bought a place in Frisco, Colorado, I rented a condo for two months, not with any intention of buying a place but instead to heal through hiking after a difficult breakup. Emery flew out from Kansas City to drive home with me at the end of my stay. We hadn’t seen each other for two months, so were anxious for ten hours of catch-up time on the road trip home.

On our last night in Frisco, we went out to dinner at one of the small restaurants on Main Street, I had come to love and wanted to share with Emery. Midway through our dinner, it started raining hard. After a few minutes, the rain stopped, and the sun came out, casting an early evening light that was even brighter than before. Experiencing rainstorms that move in and out quickly are common in Colorado, but this rainstorm was followed by something I had never seen before. It wasn’t what was forming in the sky after the rainfall, but rather what was happening inside the restaurant. There was a mass exodus to the sidewalk out in front. Waitresses set down trays of hot food, customers left their meals, and even the cook came out and took his place in the line-up of people forming on the sidewalk. When I asked someone what was going on, she shouted as she made her way to the door, “Rainbow!” And so Emery and I left our dinners and followed, falling into the line-up of people on the sidewalk with their necks craned to the sky, witnessing the spectacular rainbow forming after the storm. I had never seen anything like it. Time stopped. We stood shoulder to shoulder on the sidewalk, our eyes to the sky in awe. It was a gift, both in the presence of the arch of color in the sky, and in it being significant enough to stop people from what they were doing to witness it and share the energy of Mother Nature without explanation. I was awed by the awe. After a few moments, everyone returned to their tables, trays and cookstove, resuming where they had left off. Emery and I looked at each other with wide eyes and nodding heads as we tried to grasp what had just happened. In later years, when we would see a rainbow together, one of us would always ask, “Remember that night in Frisco?” And the other, before the sentence had been completed, would answer, “Yes. I sure do. Pure magic.” It became the benchmark by which all other rainbow moments were measured.

In the same way that Emery and I evacuated our dinner that night in Frisco, Arlo and Muna had done the same, bringing me into their experience. I loved that they held the same awe and curiosity with rainbows that their mama and I had. It was one more thread of connection. One more thread of Emery that would continue with them.

I held that moment, next to my grandchildren, Emery’s children, while we stood on the wet sidewalk, and looked to the sky while our food got cold. I felt Emery’s presence and I know Arlo and Muna did as well.

When we got back inside the restaurant, I noticed Arlo’s T-shirt. It had a rainbow on it. I told him I thought his shirt might have brought us good luck. He nodded with confidence and said, “Yes, I know that, Laudie. I got your rainbow with my shirt.”

I’m relieved that my growing-up-too-quickly-only grandson still holds the magic in the way he sees the world. Several months ago, his class was making Mother’s Day gifts. The teacher gave him the opportunity not to participate, but he told her he wanted to, even though his mama had died. She told the students it would take a few days to complete and asked them not to tell their mothers, as it was meant to be a surprise. Arlo told her that it would be a problem, as his mom already knew because she was always with him. I was deeply touched by those words when they were shared with me – sweet and bittersweet. I thought about that while standing next to Arlo and Muna looking at the rainbow, and knew that Emery was with us, sharing the moment. It felt like a little bit of comfort, but mostly it felt like love.

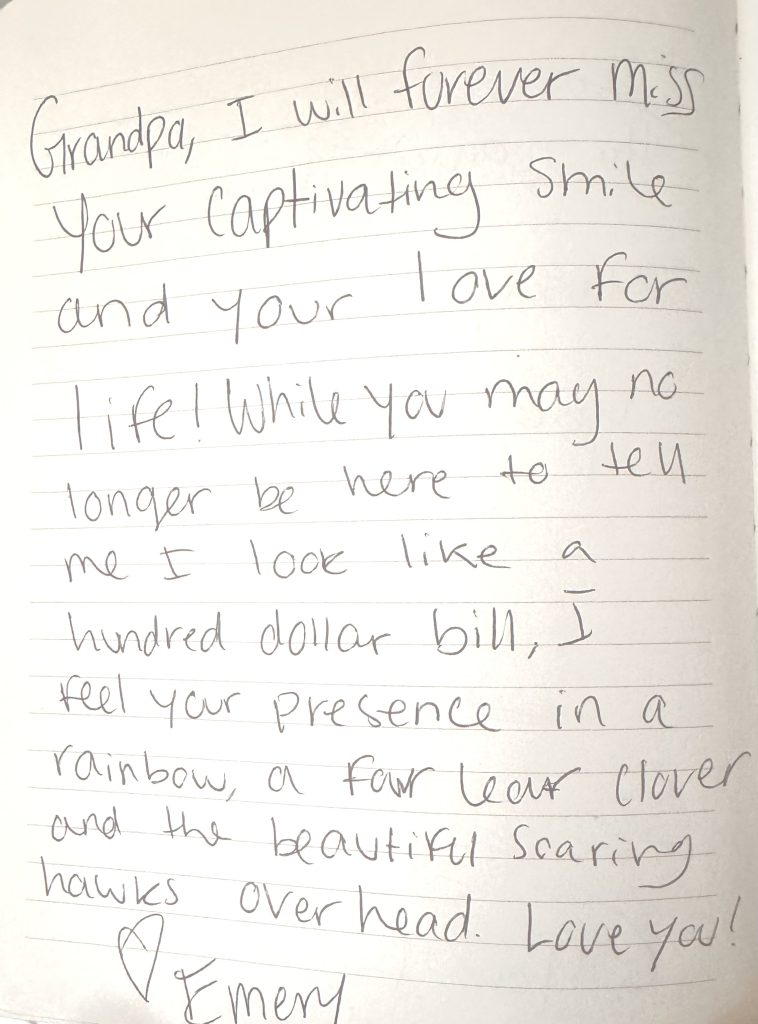

While I was going through my photos in search of the Frisco rainbow photo for this piece, I came across this gem. Emery wrote it in the book we had at Dad’s celebration of life last September. I had completely forgotten about it. Things appear when I need to see them. Rainbows just become a little more special to me.