Emery’s first steps, on her first birthday.

Emery knew immediately that it was the birthday cake she wanted when she saw it in the bakery case. I suggested the cake with the teddy bear on it, because it seemed more appropriate, but it wasn’t what she wanted. She was almost four. She wanted the pink baby bootie cake that would likely be served at a baby shower.

I was having coffee with my friend, Donna, and her almost four-year-old son, James, when Emery spotted the cake. I loved her enthusiasm, but told her it was too early to buy the cake, as her birthday wasn’t for a few weeks. I figured she’d forget about the cake or it would be gone by our next visit. I should have known better. The next time we were in the coffee shop/bakery, the pastel pink cake was still there, along with Emery’s enthusiasm. The third time we saw the cake, we ordered one.

“ The teddy bear cake sure is cute… are you sure about the baby bootie cake?” I asked Emery.

She looked at me as if I hadn’t been listening to her. She knew exactly what she wanted and wasn’t going to be swayed by my suggestions. A few days later, on her birthday, Emery blew out four candles on a pastel pink baby bootie cake.

During a time when I’m holding on so tightly to every memory that comes to mind because forgetting feels like losing more of Emery, I’m grateful for the baby bootie cake and not the teddy bear cake, because it was a cake that gave me a story and a memory.

Memories of Emery (and yes, I’ve noted the rhyming aspect and it means even more to me now) hold so much more weight than they used to, and insignificant details loom large to keep me up at night. Who came to the party at our house when she was six? Or was it seven? And what was the name of the tall girl with long hair who felt bad because she didn’t bring a gift to that party? The girl whose mom always looked tired and gave the toddler sister small tins of Vienna sausages for a snack. It doesn’t matter, yet it matters so very much. Did Emery prefer chocolate cake over vanilla cake? I feel like a part of her is fading away if I can’t remember. Then again, if I could text her, she likely wouldn’t remember either, except the Vienna sausages, which always made us laugh.

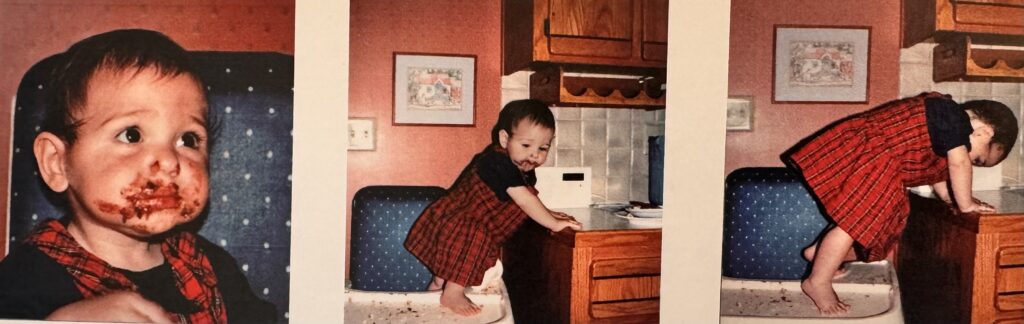

I remember Emery’s first birthday because it was also the day she took her first steps. Not steps with me seated on the floor with outstretched arms, but rather, steps across the kitchen countertop after she climbed out of her high chair (I no longer buckled her in, third child and all). I don’t remember her blowing out a candle or me singing to her, but I do remember it was just the two of us in the kitchen. Charlie was out of town, and the boys were at a friend’s house. I gave her a cupcake, and we had our own little party. Even though there would be a family gathering that weekend, I couldn’t let her actual day go by without some acknowledgement.

I remember chocolate on her face as she made her way out of the high chair, pulled herself onto the countertop, and took her first steps. I also remember the moment when I grabbed my camera, without taking my eyes off of her, to record the moment. It may not have been wise, but who would have believed me had I not obtained the evidence? I caught a glimpse of the child Emery was becoming…fearless, curious, and determined.

Age 13. After much persuasion, I caved and said yes to a slumber party for 13, because it has to be 13 girls for my 13th birthday party, Mom! We converted the basement into one big sleeping area with blow-up beds, sleeping bags, blankets, and pillows. It was worth every sleepless moment for the many stories that followed.

Age 16. Emery had a Black and White party with three other friends whose birthdays lined up consecutively on the calendar. The guests wore black and white. I had a cake made with all four of the birthday kids’ photographs in icing on the top. Emery thought it was fancy. I had to agree.

Age 20. I wasn’t in the country, but I sent my birthday wishes to Emery from the Himalayan Mountains while on my trek in Nepal with my sister, Susan. Susan and I were sitting outside our hut early in the morning in our pajamas, with our morning coffee in the foothills of the Annapurna Range, sending Emery happy birthday wishes in a phone call. Emery thanked me for the call and loved that I was calling her from the other side of the world, then reminded me that her birthday wasn’t until the next day. I was a day early due to the time change.

Age 21:

(Excerpt from a letter I gave Emery on her birthday)

Before I left the hospital to give birth to you, your brothers, ages 3 and 4 1/2, told me not to bring home another brother, and if I had a boy, to leave him at the hospital. They only wanted to be brothers to a little sister!

You brought a balance of feminine energy into a house that was overloaded with testosterone and gave your brothers the gift of growing up with a little sister. You’ve become my travel buddy, my confidant, my excellent listener, and at times, my memory. My life is richer, deeper, and more meaningful with you in it. Oct. 1, 1990, was one of the happiest days of my life, and now, 21 years later, I’m honored to celebrate that magical day with you.

We celebrated Emery’s 21st birthday with a family dinner at The Melting Pot because Emery had always wanted to go there. Afterwards, she told me it was way too much cheese for anyone to ingest. I agreed.

Age 26. I was walking the Camino with Susan on Emery’s birthday. If it looks like there was a pattern with me being out of town or out of the country, you’re correct. Late September to early October was a good time for travel as it coincided with the many walking vacations Susan and I took. I felt terrible celebrating so many of Emery’s birthdays after the fact, but she was always very supportive of my trips. I wasn’t sure what to buy her for her 26th birthday, as shops were scarce along the Camino, but I came up with an idea while walking. I made a video with happy birthday wishes from both friends I had met and strangers I approached on the Camino. The wishes were in Spanish, French, and English, most with Australian accents. It was one of the best gifts I ever gave her. She agreed.

Age 30. I was in town for Emery’s 30th, but due to Covid, we weren’t together, so my words were my gift to her.

October 2, 2020

“I slowed down to an almost stop with you, Emery, and it was deliciously wonderful to live life at the pace and the viewpoint of a little girl who twirled her way through life with a smile on her face and a song in her heart. Your deep-rooted compassion for others, both two-legged and four-legged, touched me deeply when you were a child and still does today. Thirty years ago, when Dr. Thomas handed you to me, my life felt complete. I had my girl.

Hold on to the wonder you found so early in life as you dance your way into a new decade, my darling girl. My heart explodes with the love I have for you: beautiful mother, beautiful wife, beautiful daughter. You are a gift to the world, and we are all blessed.

Recently, I was texting a friend about Emery’s birthday in October. Her daughter died five years ago.

“Do I say celebrate?” I asked her.

“Yes,” she said, “because we will always celebrate the day our girls were born.”

Celebration is still a difficult word to use for the first birthday that our family will experience without Emery, but I am holding tight to her words… celebrate the day she was born.

After being out of town or country for so many of Emery’s birthdays, I will be where I need to be on October 2nd this year. I’ll be with her brothers and their families on a beach in southern California. If I could find a pastel pink baby bootie cake, I would buy it and light the metal sparkler candles I recently found in a basket on one of my kitchen shelves. I have no idea where the candles came from, but ironically, there were two, a five, and a three. I thought, how odd, then I turned them around—a three and a five. Thirty-five. The age I was when I had Emery, the age Emery would have been this year.

October 2, 2025. We’re celebrating your birth, my darling girl, and the gift you gave to all of us who loved you. I found the perfect birthday card for you months before you died, which I set aside because that’s what I do. It’s in a small stack of cards that are separate from my larger stash, as none of them will ever be sent, but will be reread often by me; a Mother’s Day card, a Father’s Day card, a birthday card for Dad, and one for you. You are missed beyond measure and so very loved.